Dreamland

By Stephen Maine

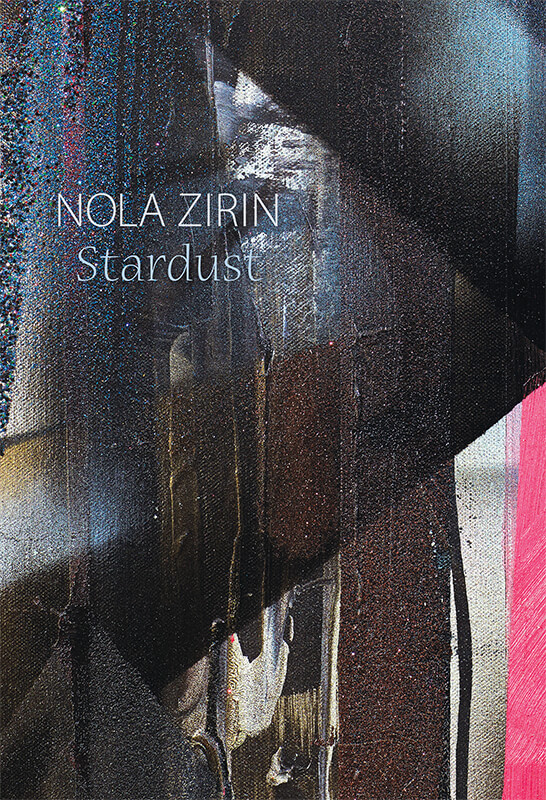

(essay for the exhibition catalog, Nola Zirin, Stardust, December, 2013 at June Kelly Gallery, NYC)

The skillful combination of atmospheric effects and crystalline forms in the recent paintings of Nola Zirin suggests a destabilized space in which structures seem to become disjointed, begin to dissolve, and hint at how they might again reconstitute themselves. Each of these commanding works draws the viewer into an endlessly self-reconfiguring environment where spatial relationships are not fixed, no form is without its qualifiers, and even the shadows have shadows. Despite the decisiveness with which the artist subdivides the surfaces of her paintings, curtails her palette and lays down her oil paint, spray enamel and glitter, she nevertheless achieves a sense of restlessness. Syncopated, urban rhythms and metropolitan light, both long present in Zirin’s work and the subjects of previous commentary, have by no means faded. But now a certain otherworldly quality has been brought into play, and the new work luxuriates in this heightened strangeness.

A crucial means to this end is Zirin’s use of the spray gun in conjunction with stencils both fabricated and found. The technique allows for drifting, soft-focus clouds of tone that terminate at clear, unequivocal edges. In the chromatically restrained Inventions #23, the grid, which Zirin often relies upon as a compositional starting point, is pried apart and broken into dissimilar sections—glyphs made of right-angled bars, shaped like H, L, F and some non-alphabetical variants thereon—that seem to drift in and out of focus, dispersed in a grayish haze along with an intermittent zigzag motif that reads as accordion folds or two-way arrows. But their behavior is complex; fugue-like, these shards of pattern and theme seem bound by an internal law of attraction that will eventually unite them in some unforeseen way.

Zirin is committed to abstraction, but her finesse at achieving vast pictorial spaces through geometric means can lead to a reading of her pictures that relies on the genre of cityscape to find its bearings. With shafts of yellowish light that pierce the surrounding gloom, Voyager implies a nocturnal world of hidden identities, veiled motives and even a distortion of time itself. “Before” and “after” is but one way to interpret the left/right bifurcation of this painting, in which ornate arabesques and a liberal application of glitter face off against a region of taped lines suggesting fantastic architecture, a futuristic city. The emotional scale of this physically smallish painting is operatic.

A strategic use of color is also present in Suspension, in which an aggregation of vigorous, parallel edges, dramatic angles and gently curving drips is anchored in the lower right corner by a vertical green-gray band flanked by magenta; it sizzles. The painting’s title may refer equally to bridges and disbelief; the painting’s primary demand is that the viewer sufficiently trust the structural integrity of this speculative edifice to venture into its hybrid of reticulate forms and plunging vertical space.

The title of Super-8 evokes an altered state of consciousness—that reverie particular to the experience of the cinema—as does as a dominant, central shape approximating the profile of a reel-to-reel film projector. Near the bottom right corner of this canvas is a tiny, flaring flood of white light like such a projector might make. An homage to the film format often associated with both home movie-makers and auteurists, Super-8 refers to the image-producing technology that has provided many of Zirin’s generation with a vivid waking dream life.

Shifting degrees of clarity characterize memories as well as images. When she was a young girl growing up in Brooklyn, Zirin would go with her family to Coney Island on her birthday, and then have dinner in Chinatown. The artist has a small but treasured cache of picture postcards of New York’s seaside playground, published in the early years of the previous century. Luna Park and Dreamland, Surf Avenue, the elephant ride, the Ferris wheel and Harry Houdini appear in these postcards, which Zirin identifies as her greatest inspiration.

Following in the tradition of geometric abstraction, to which she makes a personal and idiosyncratic contribution, Zirin finds ample space to operate between the valences of “pure plastic art” that was the object of Mondrian’s pursuit, and of Malevich’s, where “nothing is real except feeling.” She knows her materials, but she also knows that mastering them is merely an exercise unless in so doing she transports the viewer—and herself—to a place both familiar and strange. Like the Coney Island of her childhood memories, her paintings are simultaneously in sharp focus and elusive, just beyond the reach of rationality.

Stephen Maine